Respite

a new kind of app blocker

doomscrolling, and the mechanics of addiction

i watched a video on youtube a couple months ago that talked about the mechanics of addiction. as is well known, tolerance is when the response to some addictive substance or behavior is no longer as intense due to continued usage. but an interesting element of addiction is that you can approach a point where the activity barely produces a pleasurable response at all. but because of the habit that has formed, upon presented with the trigger you instinctively repeat the activity even though you are aware that it’s no longer satisfying.

this is what i believe is behind “doomscrolling”, which refers to the process of not being able to stop scrolling on social media even though you are aware that you aren’t having fun.

we’ve become so conditioned to the use of our phones that given any moment of time where we aren’t doing anything in particular, we automatically pull out our phones and start scrolling.

the need for a barrier

the main issue is not necessarily the length of usage. a lot of app blocking mechanisms rely on usage time as the main marker of progress. you are expected to set usage goals and try to meet them over time.

however, i don’t think this actually solves the root issue, which is that the time we spend mindlessly scrolling is not intentioned usage. we are being dragged along by the force of habit without the ability to consciously intervene before we begin to waste another hour on TikTok or Instagram reels.

the main goal of my app, in addition to app blocking functionality which is already common, was to prompt users to reflect on why they are trying to use an app before they do so.

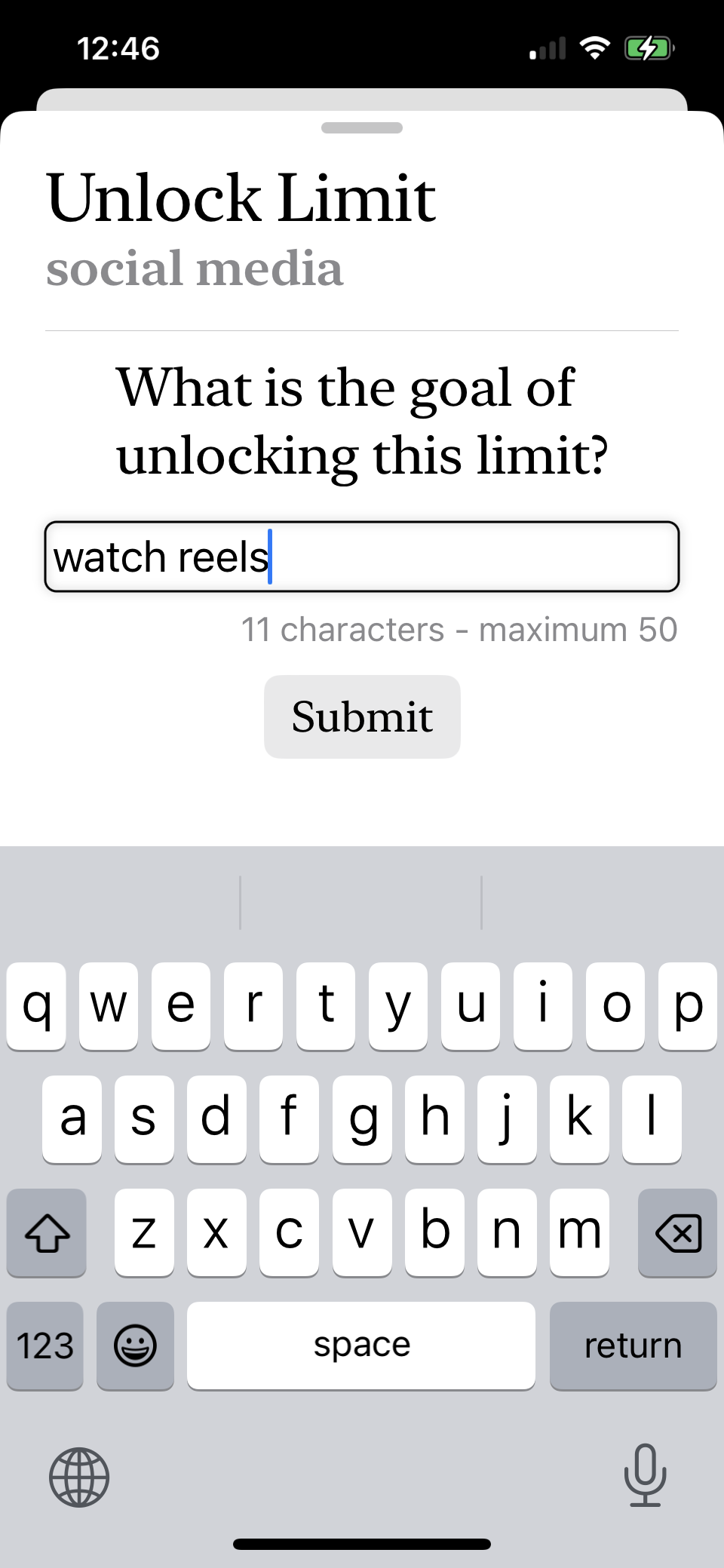

the user is first prompted for the reason why they are trying to unlock a specific app group. by actually typing out a reason, the user is forced to reflect on their intention instead of opening the app without thinking.

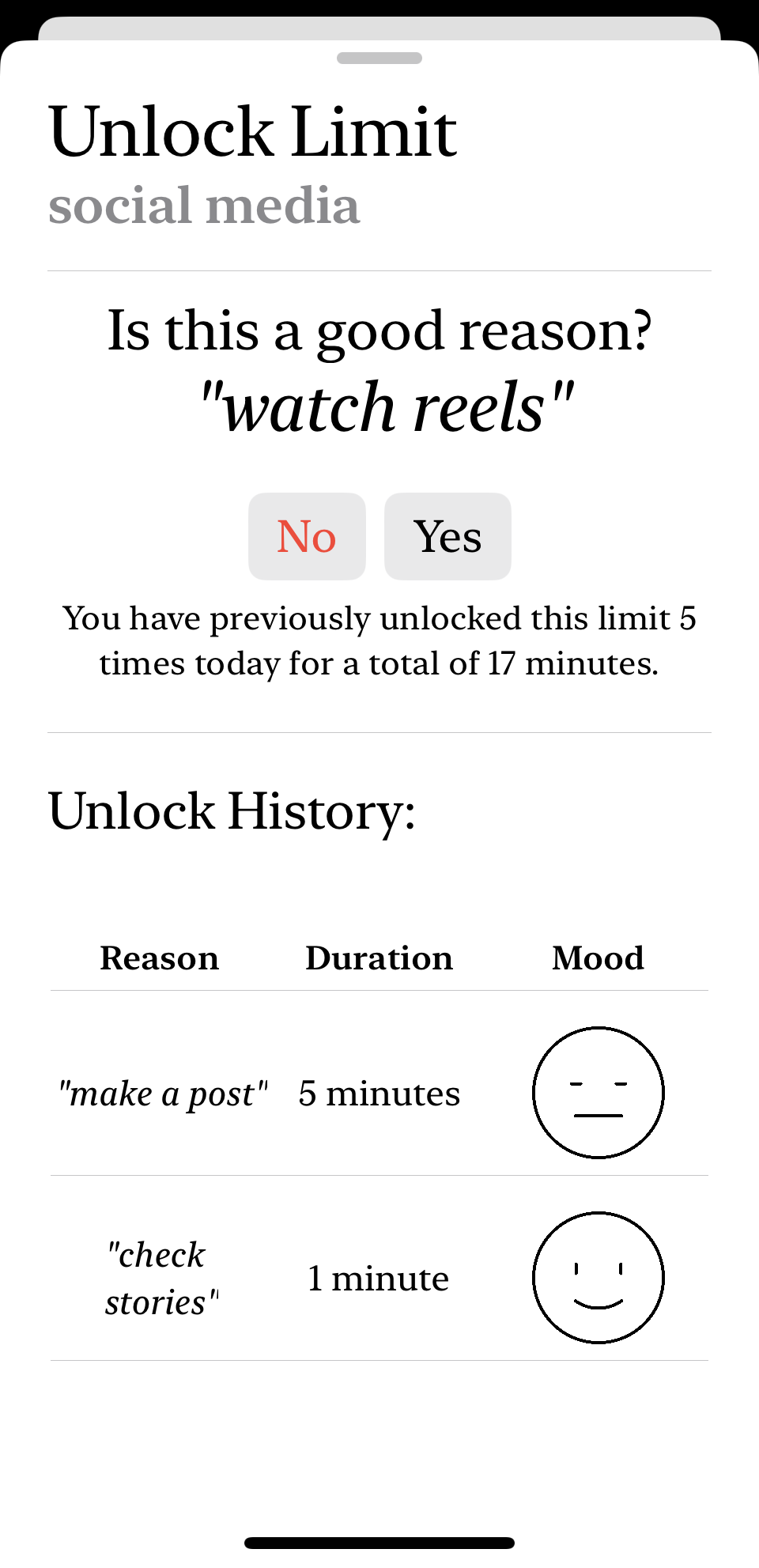

the user is then asked to confirm whether this reason is a good one, and also presented with their usage history for the day. this is so that the user can reflect on whether they past usage experiences for the day were positive or negative, and use that to make a decision.

finally, after the usage period is over, the user rates their experience on a simple 1-5 mood scale.

i later found out that there was a study which experimented with a similar app-blocking system for teens, and it was found to be effective.

development

because it was intended to be a summer project, i was targeting a lightweight app which could be completed in 2 months. the final development time came out to almost exactly 2 months from brainstorming to the app store launch.

for a while i was tracking how much time i spent working on the app using a productivity timer but eventually i racked up so much time not using it that i ditched it all together. but the app reports 98 hours of tracked work time, and i suspect the actual time spent is nearly double that.

in the beginning, the greatest challenge was just becoming familiar with the swift language. i started by copy-pasting bits and pieces from various tutorials but eventually reached a level where i was writing and using my own components.

for each page, i began by working out the placement of all the UI components, then adding in the necessary logic. at times, the UI would present some weird challenges with random padding and visual deformities but overall, it was not a problem.

the real headache was in figuring out the logic behind the app’s main functionality, which is to schedule blocking and unblocking periods for selected apps.

software design

the first challenge was to figure out how i was going to organize my code. i began by using MVVM without much thought, but eventually began to feel that trying to make ViewModels for everything other than code that displays a UI element was maybe not the best idea. i did some research and found that there was a vocal group of people online who are opposed to MVVM for SwiftUI. but at that point, i wasn’t sure what i could use instead so i decided to keep it simple and just try to separate the business logic from the UI code whenever possible, without worrying about whether something should be a “view model” or not.

the last part of the puzzle was the data model for the various data structures i used, which was pretty straightforward.

storing data

from the beginning i had decided that the app would not have a real backend, and would not require creating an account to use.

a lot of the app-blocking apps i tried when doing initial research force you to create an account to begin using them, which i think can be an additional barrier for many. the goal of an app like this should be to make the process of imposing self-restrictions as painless and simple as possible; the more complicated it gets, the more psychological resistance must be overcome.

so all the data on the app had to be stored locally, but there weren’t too many data structures that needed to be saved.

i first used the UserDefaults framework which is a key-value store built into Swift, which worked. however, UserDefaults is really meant to store user settings and other defaults, so i decided to migrate to JSON.

because they were both key-value stores, most of the code for saving the data was recycled.

another small issue that came up was how to share data between the main app and the app extensions. fortunately, by using shared containers within an app group, i was able to write the data to a location that the app extensions could access.

screen time API

i quickly realized that apple’s documentation for their APIs is not great. either that, or i was not great at understanding how to use them from the docs.

there was a large amount of trial and error where some functionality would break for no apparent reason. i would look up the issue on the apple developer forums and find that other people had the same issues but no one had a clear solution.

an additional obstacle was that because of the sensitive nature of usage data, the Screen Time API is designed to be opaque. because of this, it was especially hard to figure out sometimes whether the bug was coming from my code, or from some quirk in how iOS was choosing to execute the API calls.

for example, i found that during debugging, the OS would sometimes kill my extension which of course would break the app. the first time this happened i couldn’t figure out why for a while, even though i tried rolling back to earlier commits. but Xcode does provide a way to see device logs, and through that i found that the OS was killing my app extension.

app store launch and afterthoughts

testing

before i launched on the app store i did some testing to see if there were less intuitive bugs in the app.

along with myself, i had some friends and family download and test the app through Testflight. because different people used the app differently, it was very valuable to get feedback and bug reports from various sources.

after a couple test builds, i submitted the app for review, which was approved after roughly 2 1/2 weeks.

main takeaways

overall, the process of making an app from start to finish was very eye-opening and forced me to develop a deeper understanding of what goes into building a larger application. even though my app is relatively very small, it was still larger than any project i have done for school.

the greatest challenge is really the process of integrating the new into the old. i attempted to strike a balance between speed and throughness/good design.

if i just wrote code to try to get a feature to work, i could make progress pretty quickly. however, there would come a point where the structure sort of like a misshapen Jenga tower where some of the levels just had one block supporting everything above it. and some point, it was clear i would reach a point where it would be impossible to add something new without the whole thing breaking.

so i would go back and refactor everything, which happened a couple times. the moral of that story was that it’s better to write more thoughtful code from the beginning instead of writing sloppier code which will have to be rewritten later anyways.

another thing was that i would find myself writing duplicate code, or code that was just slightly different from another section i had written earlier. but even though i was aware of this, i did now know exactly what features existed in the language itself to create reusable code. this is because i did not really have previous training in Swift; i just jumped right in.

for a while, i did not write my own Views. i just used only the Views provided by the standard Swift library and this led to a lot of semi-duplicate code. eventually, i realized i could factor those parts out into my own Views which take their own arguments.

conclusion

overall, i have mixed feelings about my experience using the Swift language itself, but i did enjoy the process of diagnosing and solving problems. the next project i plan to work on is a concept website using the JS stack. i hope to learn more about backend development in addition to fleshing out my understanding of frontend design more.